Should This Marriage Be Saved?

By LAURA KIPNIS

CHICAGO

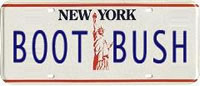

Marriage: it's the new disease of the week. Everyone is terribly worried about its condition, though no one can say what's really ailing the patient. Others are simply in denial, like President Bush, who insisted that heterosexual marriage was "one of the most fundamental, enduring institutions of our civilization" in his State of the Union address last week. Yet this statement came shortly after his own administration floated a proposal for a $1.5 billion miracle cure: an initiative to promote "healthy" marriage, particularly among low-income couples. And what of all the millionaires in failing marriages or fleeing commitment? Where are the initiatives devoted to rehabilitating this afflicted group? Sorry, they're on their own in the romance department. In this administration, the economic benefits filter upward, the marital meddling filters down.

The administration may think that low-income Americans need to be taught better communication and listening skills, but actually they're communicating just fine. Conservatives just don't like the message being communicated, which is this: We don't want to get married.

More and more people — heterosexuals, that is — don't want to get or stay married these days, no matter their income level. Yes, cohabitation is particularly prevalent in less economically stable groups, including the women counted as unmarried mothers. But only 56 percent of all adults are married, compared with 75 percent 30 years ago. The proportion of traditional married-couple-with-children American households has dropped to 26 percent of all households, from 45 percent in the early 1970's. The demographics say Americans are voting no on marriage.

The fact is that marriage is a social institution in transition, whether conservatives like it or not. This is not simply a matter of individual malfeasance; in fact, it may not be individual at all. The rise of the new economy has gutted all sorts of traditional values and ties, including traditions like the family wage, job security and economic safety nets. Women have been propelled into the work force in huge numbers, and not necessarily for personal fulfillment: with middle-class wages stagnant from the early 70's to the mid-90's, it now takes (at least) two incomes to support the traditional household.

But as the political theorist Francis Fukuyama has pointed out, the changing nature of capitalism since the 1960's also required a different kind of work force; it was postindustrialism, perhaps even more than feminism, that transformed gender roles, contributing to what he calls the "great disruption" of the present. The increasing economic self-sufficiency of women has certainly been a factor in declining marriage rates: there's nothing like a checking account to decrease someone's willingness to be pushed into marriage or stay in a bad one. And interestingly, welfare reform has played the same role for lower-income groups: studies have shown a steep decline in marriages among women in welfare-to-work programs, for many of the same reasons.

So how about a little more honesty and fewer platitudes on the marriage question. Sure, most people would like a lifetime soulmate, but then there's that widely quoted 50 percent divorce rate to consider. If more people are resisting marriage, or fleeing the ones they're in, or inventing new permutations like cohabitation and serial monogamy, here's one reason: for a significant percentage of the population, marriage just doesn't turn out to be as gratifying as it promises.

In other words, the institution itself isn't living up to its vows. A 1999 Rutgers University study reported that a mere 38 percent of Americans who were on their first marriages described themselves as actually happy in that state. This is rather shocking: so many households submerged in low-level misery or emotional stagnation, pledged to lives of discontent. But perhaps there's also a degree of social utility in promoting long-term unhappiness to a citizenry. After all, those accustomed to expecting less from life are also less accustomed to making social demands - and are thus primed to swallow indignities like trickle-up economics along with their daily antidepressants.

As for those better communication skills the Bush administration wants to teach low-income groups, particularly regarding "difficult issues" like money: that could backfire. If the lower and middle classes did start communicating better about money, that could include communicating to their elected representatives that they're fed up with condescension and election-year pandering for conservative votes while central issues in their lives like jobs, pay and working conditions are studiously ignored.

But you can also see why conservatives might be getting nervous about the marriage issue. According to the historian Nancy Cott, marriage has long provided a metaphor for citizenship. Both are vow-making enterprises; both involve a degree of romance. Households are like small governments, and in this metaphor, divorce is a form of revolution - at least an overthrow. (Recall that our nation was founded on a rather stormy collective divorce itself, the one from England.) Come November, how many of the disaffected might start wondering if they'd be better off with a different partner? How many will find themselves murmuring those difficult, sometimes necessary (and occasionally liberating) words: "I want a divorce"?

We're a society whose social institutions are in flux, and the interplay among economic transitions, shifting gender roles and changing emotional expectations are impossible to quantify until the dust settles. If the Bush administration really wants to improve the lives of low-income people, here's some simple advice: Rather than meddle in their love lives, raise their incomes. Start by throwing that $1.5 billion into the pot. Once low-income groups are making middle-class wages, their marital ambivalences will be their own business, just like millionaires. Or members of Congress. Or all the rest of us.

Laura Kipnis, a professor of media studies at Northwestern, is the author of "Against Love: A Polemic."

Posted by P6 at January 25, 2004 08:21 AM

Trackback URL: http://www.niggerati.net/mt/mt-tb.cgi/110

Comments