Administration's Message on Iraq Now Strikes Discordant Notes

By DAVID E. SANGER

WASHINGTON, Feb. 6 — It will be more than a year before the country hears the conclusions of the commission that President Bush reluctantly appointed on Friday to examine what has gone wrong with American intelligence collection.

But in recent days, it has been obvious in Washington that something has also gone awry in a White House that prides itself on never wavering from its message, especially when the subject is Iraq. At moments, Mr. Bush and his national security team — badgered for explanations about whether the country would have gone to war if it knew then what it knows now — have sounded as if these days, it is every warrior for himself.

Rather than uniform and disciplined, their answers have been ad hoc and inconsistent. And the result is that the president appears very much on the defensive just at a moment when his aides thought he would be reaping the political benefits of ridding the world of Saddam Hussein.

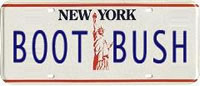

[P6: The answers have ALWAYS been ad hoc and inconsistant. But at leastthe SCLM seems to be waking up.]

"It's been a bit of a cacophony," one national security official at the White House acknowledged Friday. "Maybe the naming of the commission will smooth it out."

The change in pitch began with Mr. Bush himself, who in the heady days after Mr. Hussein's fall regularly declared that it was only a matter of time before weapons of mass destruction would be found. When the chief American weapons inspector, David A. Kay, emerged from Iraq and punctured whatever remained of that confidence, Mr. Bush shifted, declaring that the war there had been the right one to fight, for reasons having little to do with any Iraqi weapons that could have been imminently used. Yet he declared his unwavering confidence in the intelligence that lands on his desk every morning at 8, and in the people who provide it.

On Friday afternoon, looking unusually ill at ease in the White House press room while quickly announcing most of the members of his commission, he acknowledged that "some prewar intelligence assessments by America and other nations about Iraq's weapons stockpiles have not been confirmed."

"We are determined to figure out why," he said, his first specific acknowledgment that he decided to engage in a preventive war last March on the basis of a flawed assessment, at best, of how urgent a threat Iraq posed to America and its allies.

Mr. Bush has not gone as far as his secretary of state, Colin L. Powell, who caused more than a few winces in the White House this week when he told The Washington Post that had he known there were no stockpiles of weapons, he is not sure he would have recommended going to war. Mr. Powell stated the obvious: "It was the stockpiles that presented the final little piece that made it more of a real and present danger and threat to the region and the world." And, he noted, "the absence of a stockpile changes the political calculus."

He was quickly reined in, but few in the State Department - or the White House - doubt that Mr. Powell, perhaps thinking about his legacy in what is expected to be his last year in office, gave a brief glimpse of his true thoughts.

Not surprisingly, Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld has been the most combative, saying that if Mr. Hussein could hide in a hole for months on end, then surely his weapons could also hide in one.

"What we have learned thus far," Mr. Rumsfeld said, "has not proven Saddam Hussein had what intelligence indicated and what we believed he had, but it also has not proven the opposite."

Only a day later, George J. Tenet, the director of central intelligence, conceded that the C.I.A.'s critics had at least half a point.

"When the facts on Iraq are all in," Mr. Tenet said, "we will be neither completely right nor completely wrong."

That assessment, many in the White House believe, may be their best talking point from this moment forward.

Even if the appointment of the commission allows the administration, at least for now, to get back on message, chinks exposed in the White House armor on this issue will not be easily sealed.

People close to Mr. Bush say he has been frustrated that Mr. Kay's assessment rekindled all the arguments that dominated the news over the summer, when the White House had to pull back from the president's State of the Union claim of last year that Mr. Hussein had sought uranium in Africa.

Mr. Bush certainly was in no mood Friday to entertain many questions on the issue of intelligence. He announced the commission's formation in a five-minute statement. He barely introduced its co-chairmen, former Senator Charles S. Robb of Virginia and Laurence H. Silberman, a senior federal appeals judge in Washington. He left the room without taking questions.

More to the point, Mr. Bush never explained whether the charter of the commission would extend beyond intelligence gathering to the politically crucial question of how the White House had used the intelligence it received. Democrats seized on the omission.

"On the one hand, the commission is charged with looking at prewar intelligence assessments on Iraq, but apparently not at exaggerations of that intelligence by the Bush administration," said the Senate Intelligence Committee's ranking Democrat, Carl Levin of Michigan. "On the other hand, the commission is tasked to look at so many other areas that it will not be able to adequately focus on the paramount issue of the analysis, production and use of prewar intelligence on Iraq."

Even some in the White House conceded that only one member of the commission - Adm. William O. Studeman, former deputy director of central intelligence - was deeply versed in both human and high-tech intelligence collection, though Senator Robb once served on the Intelligence Committee.

Also on the panel is Senator John McCain, the Arizona Republican who frequently gets under Mr. Bush's skin on questions of the deficit and other domestic issues. But he was a strong supporter of the war in Iraq, and his independent streak will most likely insulate Mr. Bush from the Democratic accusations that the president picked a panel unlikely to challenge him.

In any event, the commission's makeup seems to have been influenced more by a quest for political balance than for depth of knowledge about the challenges facing the turf-conscious intelligence agencies. That is in sharp contrast to the last major investigative panel that the administration appointed, to examine the disaster involving the space shuttle Columbia. That panel had specialists on composites and propulsion, organizational dynamics and safety, along with experts who spend their lives thinking about the future of the space program.

An equivalent panel in this case might have included experts in a variety of espionage specialties, in the difficulties of piercing secretive governments and terror groups, and in the way other nations have organized their intelligence agencies.

But then again, intelligence collection is not a precise science. And in the end, its findings merge with the necessities of politics and power.

Posted by P6 at February 7, 2004 10:57 AM

Trackback URL: http://www.niggerati.net/mt/mt-tb.cgi/285

Comments