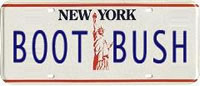

I think it pretty obvious that I approve of this sentiment.

Mark A. R. Kleiman: Avodim hayyinu l'Pharoh b'Mitzrayim

I wonder whether, now that their own oxen are being gored to right-wing applause, conservative Jews and conservative gays will reflect on the extent to which "conservatism" as a political practice in American (as opposed to the conservative strand in political thought represented by Burke, Hayek, and Oakeshott) turns out to embody a willingness -- and sometimes a gloating eagerness -- to stomp on the out-groups.[That's much less true of libertarians, with the sole -- but not unimportant -- exception that libertarians are usually willing to allow "market forces" and "free private choices" to stomp on the poor. The President's decision to make the FMA an issue in the coming election will create some agonizing choices for libertarians.]

One common, and not discreditable, reaction to being treated badly is to resist, seek revenge, and vow that no one is ever going to have the opportunity to treat you that way again. It's natural enough to generalize from oneself to a group: for a Jew, say, to resent mistreatment of Jews even if he's not personally damaged.

But the larger generalization -- from rage at being mistreated to the sense that mistreating people, and especially the vulnerable, is wrong -- seems to be less common. (Wesley Clark's claim during his campaign that concern for the unfortunate is the common core of all the great religions was edifying, but I doubt it was entirely accurate.) However, that generalization does seem to be characteristic of Jews, which is one of the things that make me proud to be Jewish.

The willingness of Jews to stand up for vulnerable non-Jews, which I had always attributed to centuries of being the out-group, turns out on closer examination to be really quite deeply rooted in the religion.

…It seems, if you think about it, a rather remarkable assertion to put at the very center of a celebratory feast. What other group, instead of boasting about being nobly born, makes a fuss about being descended from slaves, and then personalizes it so as to say that everyone present was a slave until redeemed?

But linked to the commandments in Deuteronomy, that phrase comes to mean: "We were slaves" and therefore must never, never, ever act like slaveowners. That makes sense of the empirical link between Judaism and liberalism.

No, there's no reason to think that the "liberal" viewpoint on any given policy issue is superior to the "conservative" one. With respect to crime, which is my own study, I'd have to say that the liberal tendency over the past half-century has mostly pointed toward the wrong answers, though the conservative tendency hasn't noticeably pointed to the right ones. Nor is it the case that all claims made on behalf of vulnerable groups are just claims, or even that satisfying those claims will in fact be good for the groups in question.

But I'd still rather start with a political philosophy consistent with "avodim hayyinu" than with one rooted in the impulse to defend the power and wealth of the wealthy and the powerful, and to demonstrate -- as, for example, Rush Limbaugh, Honorary Member of the House Republican Class of 1994, does so amusingly to his millions of listeners -- that despised groups are really despicable.

After all, you don't have to be Jewish to recognize the basic principle of karma: What goes around, comes around.

Posted by P6 at March 1, 2004 12:32 PM

Trackback URL: http://www.niggerati.net/mt/mt-tb.cgi/633

Comments